This page provides detailed background information on Ecology’s rulemaking to amend Chapter 173-180 WAC, Facility Oil Handling Standards and Chapter 173-184 WAC, Vessel Oil Transfer Advance Notice and Containment Requirements

Ready to take action? Head on over to Take Action – Ecology Needs to Hear from You!

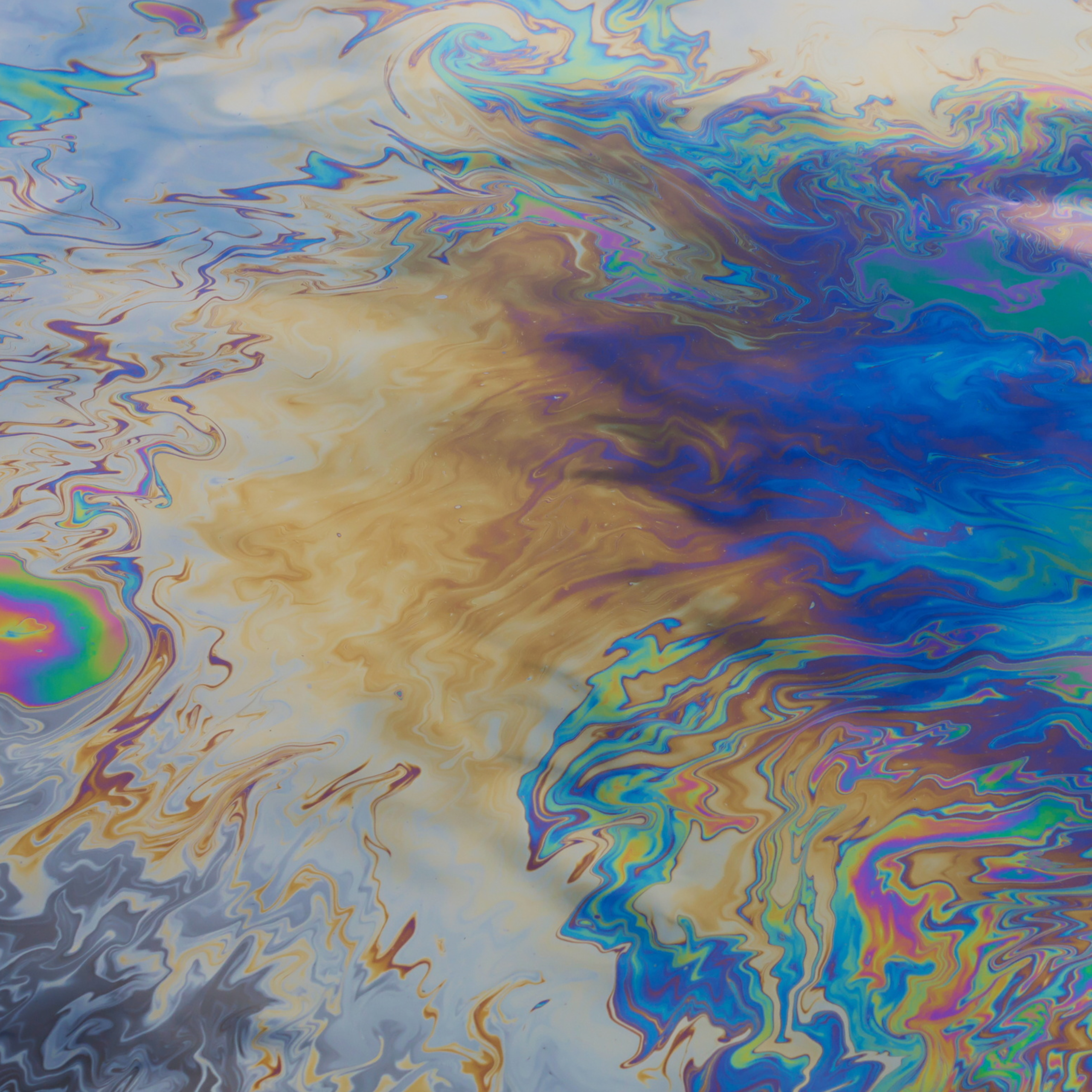

According to the Department of Ecology, each year in Washington State there are “more than 10 billion gallons of oil moved through over 12,000 oil transfers. These activities create a risk for oil spills that are toxic and pose a significant risk to Washington’s environment, economy, public health, and historical and cultural resources.” 1

Ecology’s rulemaking is a result of Washington State Legislature’s bill, ESHB 1578 – Reducing threats to southern resident killer whales by improving the safety of oil transportation (also known as the Oil Transportation Safety bill).

This rulemaking needs to include additional requirements in order to achieve the legislative intent “to reduce the current, acute risk from existing infrastructure and activities of an oil spill that could eradicate our whales, violate the treaty interests and fishing rights of potentially affected federally recognized Indian tribes, damage commercial fishing prospects, undercut many aspects of the economy that depend on the Salish Sea, and otherwise harm the health and well-being of Washington residents.”2

Here are our 3 recomendations for additonal requirements:

Require all secondary containment structures (that prevent spilled oil from reaching the waters of the state) to withstand seismic forces:

This rulemaking requires seismic updates for all transfer pipelines and storage tanks, but not for secondary containment systems. Most of the state’s refineries’ and bulk oil handling facilities’ secondary containment systems were built before 1994 and they pose an unacceptable threat in the event of an earthquake.

WA State defines secondary containment in WAC 173-180-025 (32): “Secondary containment” means containment systems, which prevent the discharge of oil from reaching the waters of the state.

Secondary containment is critical to protecting the waters of the state, including groundwater. Primary oil containment is the storage tank or pipe wall. Ecology is requiring seismic protection measure updates for refinery and bulk oil handling facility pipelines and storage tanks to “reduce the risk from seismic events” where “reduce” refers to the fact that pipelines and storage tanks cannot withstand seismic forces. New secondary containment systems are required to “withstand seismic forces,” but the draft rule does not require seismic protection measure updates for existing secondary containment systems.

Given that earthquakes will happen, secondary containment systems that are not required to be updated and maintained to withstand seismic forces will not be able to prevent the discharge of oil from reaching the waters of the state. The state knows what’s needed for earthquake preparedness and that should be required for all refinery and bulk oil handling facility secondary containment systems.

Require all oil transfer operations to be pre-boomed (when safe and effective to do so) and eliminate the Rate B loophole that allows oil transfers at 500 gallons per minute or less to occur without pre-booming.

WA State’s oil transfer operation regulations went into effect in 2007 in response to the 2003 Foss Barge – Point Wells oil spill. Just after midnight on December 30, 2003, approximately 5,000 gallons of heavy fuel oil was spilled during an oil transfer operation in Edmonds. Because the delivering and receiving vessels were not pre-boomed (to contain the spilled oil) and also because the spill happened in the middle of the night such that hours elapsed before oil spill response containment and recovery could be initiated; in less than 24 hours of the spill, almost all the oil had moved ashore damaging 400 acres of the Suquamish Indian Reservation’s prime cultural and environmental lands, including salt-water marsh, old growth timber, beaches, and clam beds.

The information provided in advance of an oil transfer helps Ecology regulate these activities and have the information needed to respond to a spill if one occurs. Pre-booming is an important oil spill mitigation measure. If a spill happens, it is contained and more easily collected before it can oil shorelines and cause extensive impacts. Note that pre-booming is prohibited for highly volatile products, like gasoline, that are an explosion hazard when contained in a boom.

Ecology’s rulemaking will update some of the requirements for oil transfer operations and reporting requirements. Unfortunately, the rulemaking doesn’t address the fact that pre-booming is only required for oil transfer operations that occur at transfer rates greater than 500 gallons per minute – a loophole too big to let stand.

Additional information about the 2003 oil spill

- Kitsap Sun. Dec 31, 2003: Oil spill darkens NK beach

- Indian Country News. Jan 14, 2004 – updated Sep 12, 2018: Oil spill damages marine estuary at Suquamish

- Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission: Suquamish Tribe’s Doe Kag Wats Healing a Decade Later

- Sightline’s article, Fifty Years of Oil Spills in Washington’s Waters, includes a section on this spill.

- From the Seattle PI. Jan 21, 2004: State considers adopting Navy strategies to avoid oil spills:

“Daylight refueling is also a hard-and-fast rule for the Navy. Exceptions are made only for special purposes when they are critical to the success of a mission, and even then require the personal approval of the admiral overseeing the Northwest-based fleet.”

Rate A vs. Rate B Oil Transfer Operations

Rate A oil transfer operations have a transfer rate greater than 500 gallons per minute. Rate A transfers require pre-booming IF it’s “safe and effective” – a determination that’s based on the current and weather conditions. Pre-booming is prohibited for highly volatile products, like gasoline, that are an explosion hazard when contained in boom.

Pre-booming is not required for Rate B oil transfer operations which have a transfer rate of 500 gallons per minute or less. Ecology staff have stated that when the law was enacted in 2007, the intent was for all cargo and fueling operations to be included as Rate A transfers. However, cargo and fueling (bunkering) oil transfer operations do occur at transfer rates of 500 gallons per minute or less with no pre-booming required – another loophole too big to let stand.

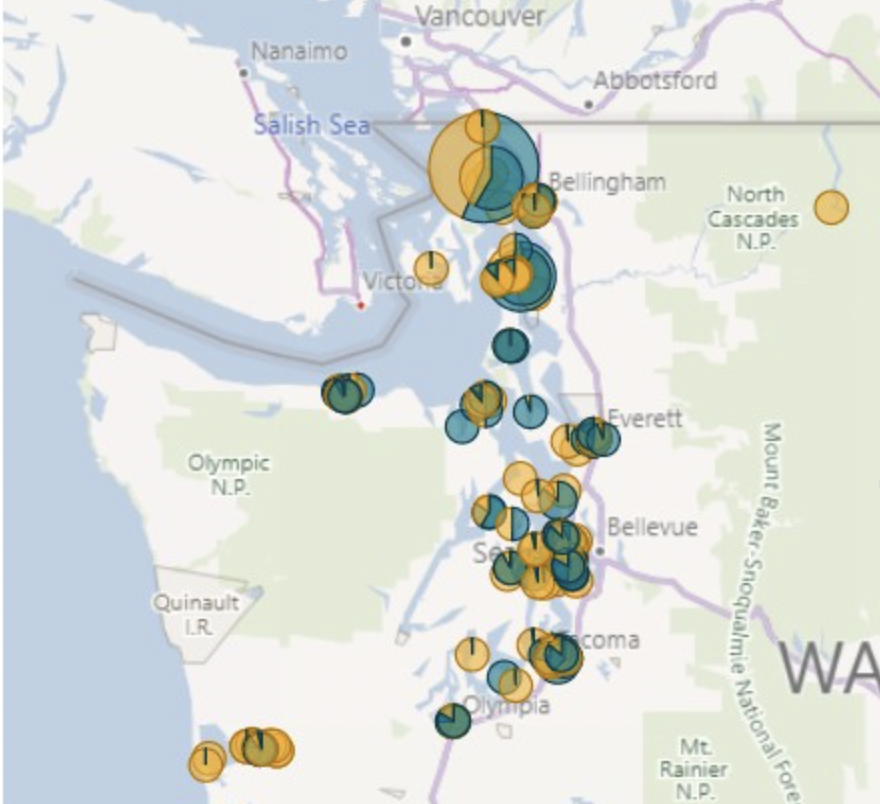

Oil transfer operations that occur over water in remote anchorage areas, and especially those oil transfers that occur without pre-booming, are especially concerning because if there’s a spill the response could be delayed by the time it takes for oil spill response resources to arrive from other locations.

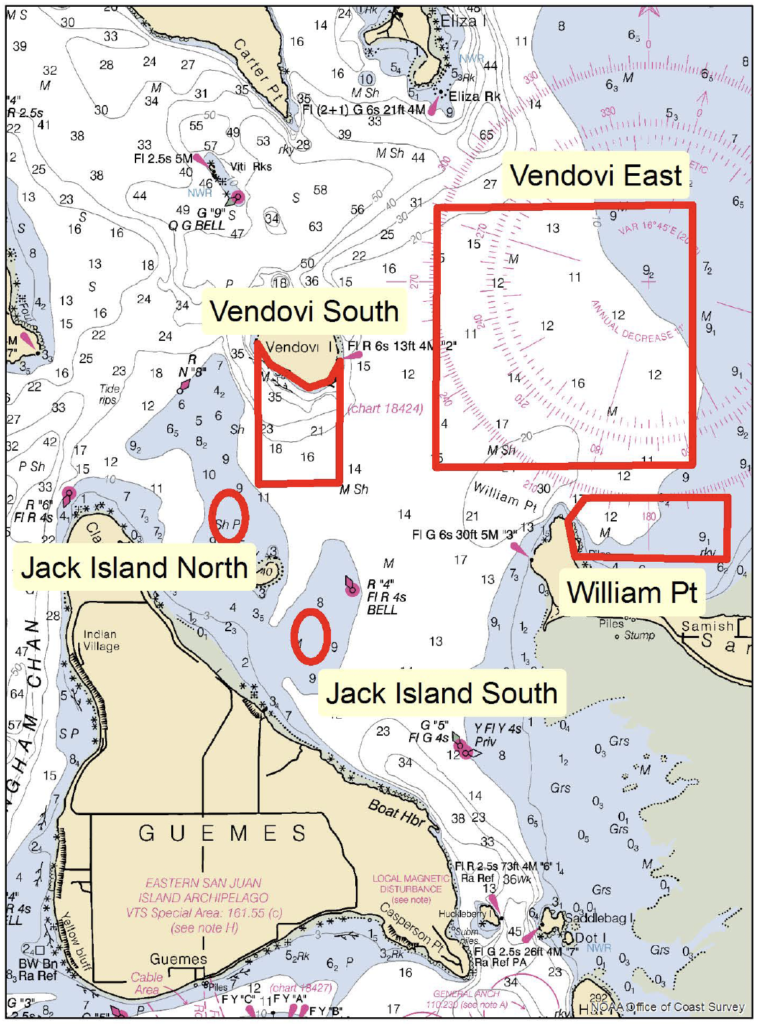

Oil Transfer Operations at the Anchorage Areas Near Vendovi Island

A good example of the increase in oil transfer operations and the increase oil spill risk and impacts are the anchorage areas near Vendovi Island. These five anchorage areas are adjacent to the locally protected Vendovi Island Preserve and Jack Island Preserve. The Vendovi Island Preserve is one of the wildest private islands in the San Juan archipelago and was a priority for permanent conservation for many years leading up to its protection in perpetuity by the San Juan Preservation Trust in 2010. In 2007, the Jack Island Preserve was protected in perpetuity by the San Juan Preservation Trust in partnership with the Nature Conservancy. The five anchorage areas near Vendovi Island are also in close proximity to the federally protected San Juan Islands National Monument, San Juan Islands National Wildlife Refuge, and Padilla Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve.

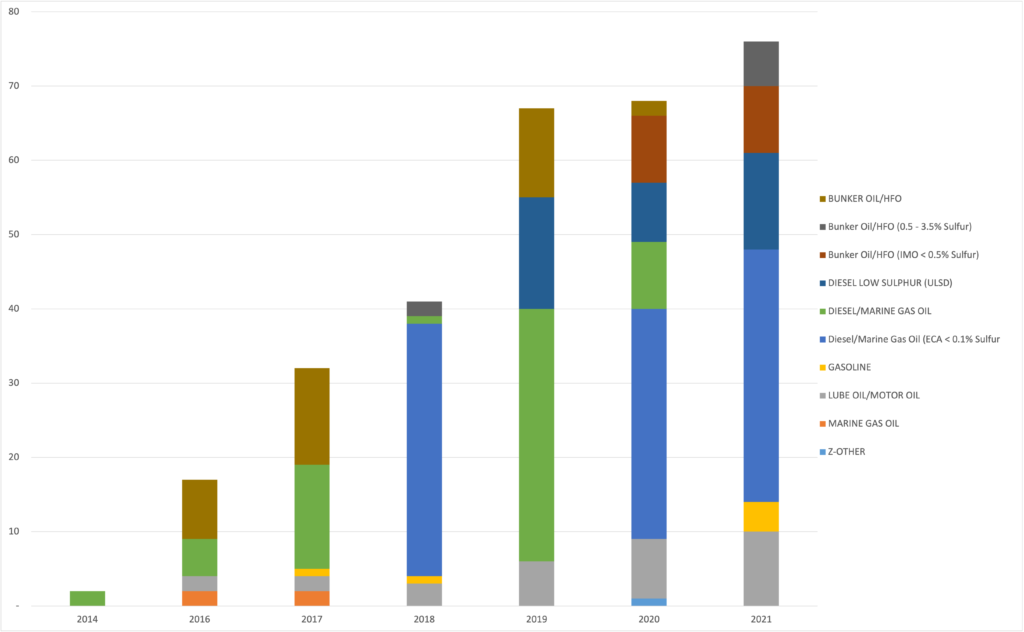

No oil transfer operations occurred before 2014 (and none in 2015) and the number of oil transfer operations has significantly increased from two transfer operations in 2014 to 76 in 2021.

Vendovi Island Anchorage Areas – Total Number of Oil Transfer Operations 2014 – 2021

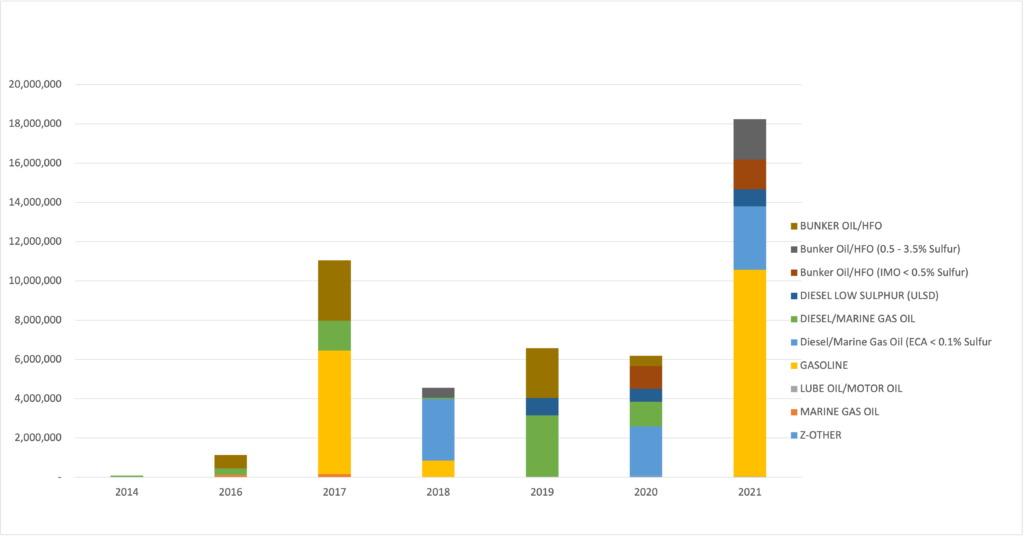

The total volume of oil transfer operations has also increased from 82,500 gallons in 2014 to 18,236,304 gallons in 2021.

Vendovi Island Anchorage Areas – Total Volume of All Oil Transfer Operations 2014 – 2021

The Rate B oil transfer operations that were not pre-boomed increased from two in 2014 to a high of 15 in 2020, and 13 in 2021; with an increase in volume from 82,500 gallons in 2014 to 705,567 gallons in 2020.

More information about oil transfer operations:

- Learn more here with Friends’ interactive tool for visualizing over-water oil transfer operations in Washington State

- Bunkering requirements for ships

- What Does The Word “Bunker” Mean?

- 33 CFR Part 156 Oil and Hazardous Material Transfer Operations

- Alaska’s pre-booming requirements for oil transfer operations do not differentiate by the rate of transfer.

Restrict all oil transfer operations to daylight hours or, at the very least, restrict all oil transfer operations to daylight hours when it’s not safe and effective to pre-boom.

An important lesson that should have been learned from the 2003 oil spill is that spills that happen at night can delay the initial spill response. See the Seattle PI article above. The delays in spill response during the 2003 oil spill resulted in significant shoreline damages that may have been avoided if the spill had not occurred at midnight and if the spill could have been contained sooner.

Restricting oil transfer operations to daylight hours or favorable weather conditions may be required when Ecology conditionally approves a facility to operate with specific precautionary measures until their operations manual is approved by Ecology. This restriction should be required for all oil transfer operations.

Footnotes:

[1] 2023-25 Budget Request — Operating, page 80. (2022). Washington State Department of Ecology.

[2] ENGROSSED SUBSTITUTE HOUSE BILL 1578. OIL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY. EFFECTIVE DATE: July 28, 2019.